Delayed Echoes: Dismantling Mental Health Stereotypes

Guest post by: Sharrae Lyon

Chain, chain, chains of pain,

The memories deep.

Silence skills the roots of love.

As a filmmaker, writer and storyteller of Xamaycan descent, my work explores how those who have been deemed inferior by Eurocentric standards—due to their skin colour, divergent worldviews, disabilities and mental health issues—claim their power as individuals. I am inspired to create work that honours the right of each human being, regardless of race, ability, gender, and/or sexuality. Through African-Indigenous perspectives that provide alternative solutions to personal, familial and societal challenges, with the understanding that it is possible to nurture healthy community bonds.

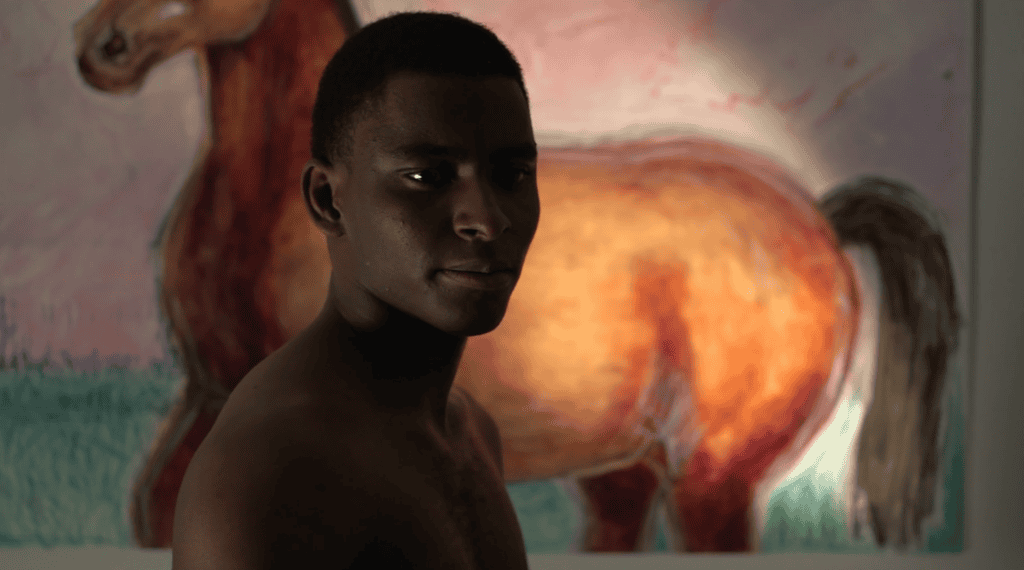

Author and filmmaker Sharrae Lyon starring as Patrice Campbell in her film Delayed Echoes.

In 2014, I launched Alien Nation, a project that is recognizes that the development and advancement of African, Indigenous and various peoples of colour has been interrupted by European conquest. I believe that it is through our subjective connections to community ideals of compassion, faith and love that we can individually and collectively overcome our challenges through song, dance and community; while ensuring integration of each member in wider society.

As part of my latest short film project Delayed Echoes, I am currently exploring how society’s labels of race and disability impact our capacity for self-definition. In the same way that race has and continues to carry both negative and positive stereotypes, mainstream society often forces stereotypes on neurodivergent people (people who are struggling with mental health issues) that push them into the margins and robs them of agency, desire, power and capacity to change.

The trailer for Delayed Echoes by Alien Nation/Sharrae Lyon.

Messiah Campbell, the main character in my film, is a 25-year-old man who is grieving the loss of his mother and struggles with the seemingly simple task of getting dressed. Messiah subsequently uses his imagination and artistic skills to create a path towards living amongst horses as a way of healing from his grief.

The process of creating this story has led me on a personal journey towards my own paternal line of great horsemen, including my great-grandfather, Mortimer “Morty” Heron. The son of a white Scotsman and black woman in Jamaica, he had the rare privilege of learning to ride horses on his father’s estate and later became the World Class Hall of Fame Jamaican racehorse trainer. To this day, the top jockey in Jamaica is rewarded the Morty Heron prize, an award created in honour of my grandfather.

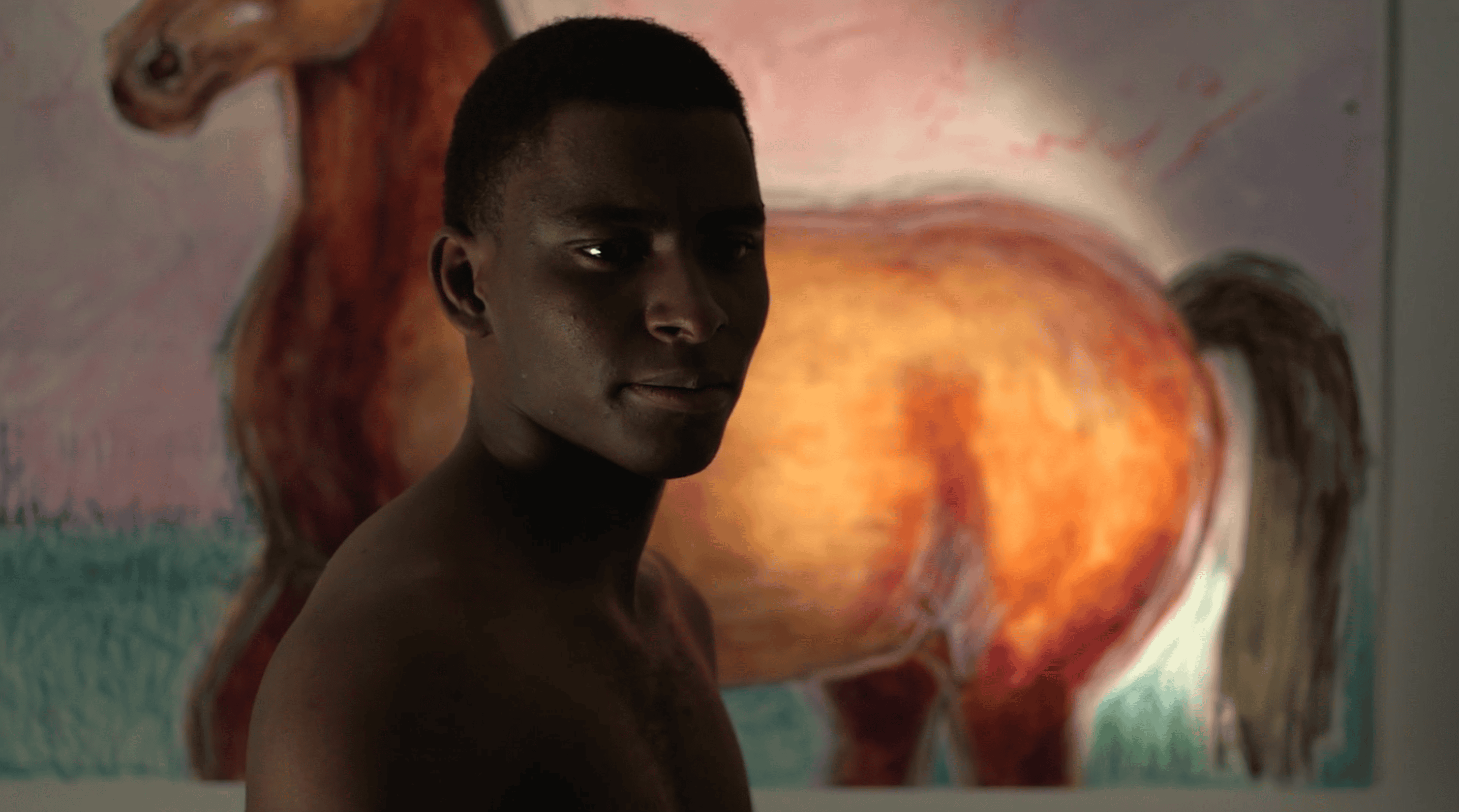

A still from Delayed Echoes featuring the character Messiah Campbell, played by Jahlen Barnes.

As I reconnect with my ancestral legacy of horsemanship, I have come to understand the powerful lessons we can learn from these creatures. Horses have an incredible way of teaching humans how their energy can positively or negatively impact their. Equine trainers and therapists describe how, as prey animals, horses must use all their senses to ensure their survival from predators. This makes them hyper-vigilant and sensitive to the subtlest changes in their environment. Equine therapists (medical professionals who use horses as part of their treatment of patients) point to the powerful link of the shared quality of sensitivity between horses and neurodivergent individuals. For human beings, this quality often manifest as anxiety, depression, symptoms of ADHD and autism.

Through my ongoing research, I have spoken to neurodivergent individuals, therapists, educators and parents of neurodivergent children including the incredible Montreal-based playwright Christine Rodriguez and the organization called Child and Youth Care Alliance for Racial Equity (CARE). At their last networking meeting, I had the opportunity to screen Delayed Echoes, which resulted in child and youth workers and practitioners sharing their approaches to creating transformational spaces for Black youth living with autism. Individuals shared their first-hand experience of witnessing how Black youth receive care that results in further isolation.

One specific story that was shared was of a young man who exhibited fits of rage. When she entered the workplace, she noticed that there were 5 individuals who would physically restrain him. However, through her work with him, his fits remarkably decreased. When asked how she managed to do it, she responded, “I listened to him.”

A still from the film Delayed Echoes.

This exchange shows that alternative solutions available to Black youth on the autism spectrum as well as their families. There needs to be changes to our mental healthcare system to ensure access to support and awareness towards African cultural perspectives to combat the stigma around neurodivergence. Part of the solution involves shedding Eurocentric and colonial perspectives and exploring how we can interact with and understand neurodivergent people through alternative lenses.

In speaking with neurodivergent individuals, it is evident there is a desire within the community for a new approach when it comes to delivering care and services to people living with ASD. Integral to these conversations is the need for recognizing that individuals—regardless of whether they can express themselves independently or not—have a very vigorous internal world with needs, meaning, fears, hopes and dreams that is no less valid than anyone else’s.